Suburban Development

“Suburbs do not pay for themselves” is the main message communicated by advocacy group Strong Towns. The logic goes like this:

When the city expands its suburbs, or a suburb expands itself, it receives a short-term influx of cash, population, and reputation. The city rarely pays the full cost for its constructions: it is often paid by the federal government, the state government, and/or the developers themselves. The city then assumes the costs of maintaining the infrastructure behind the new development - roads, water systems, sewage, and whatnot. This cost is higher than the amount of money the city receives (through property tax) from its expansion, but does not have to be paid until decades after the original construction.

Thus, the city is continually incentivized to indulge developers, if only to gain the money needed to repair older developments. In the end, the city either requires continuous bailout from the federal/state government, or it has to cut off projects, like libraries or road repair, to stay afloat.

Strong Towns calls this "The Growth Ponzi Scheme."

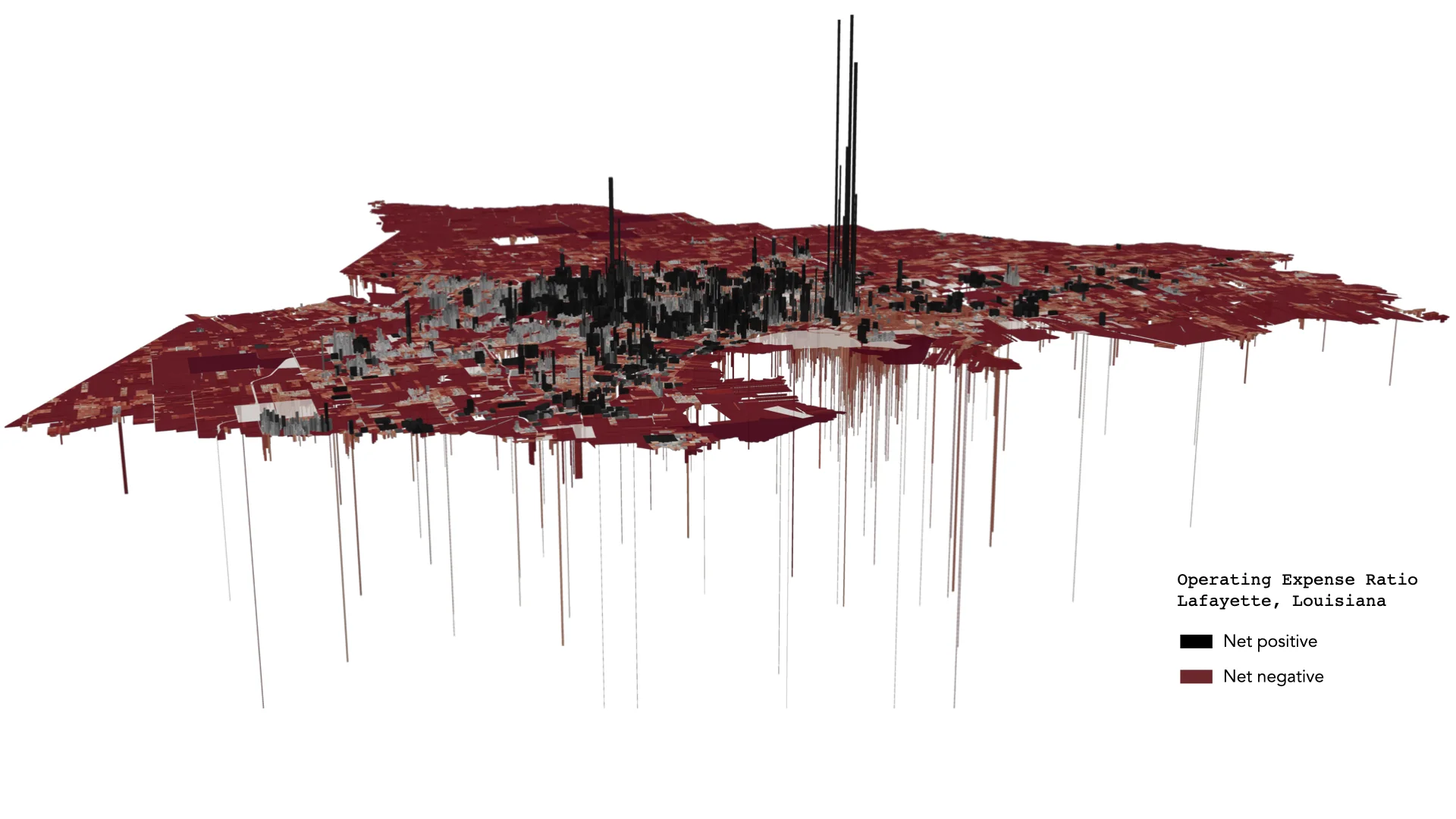

Urban3 is another organization, though it does tax analysis contract work for cities rather than being a nonprofit. Its claim to fame is its data visualization. Here’s an example:

You can see pretty clearly where downtown is - and where the city is losing money. Certain land uses cost far more for infrastructure than they pay. When people think of suburbs, they often think of the housing, but this shows that suburban businesses also lose the city money, or come in at around neutral. The downtown is left to pick up the slack, and it cannot do enough to help.

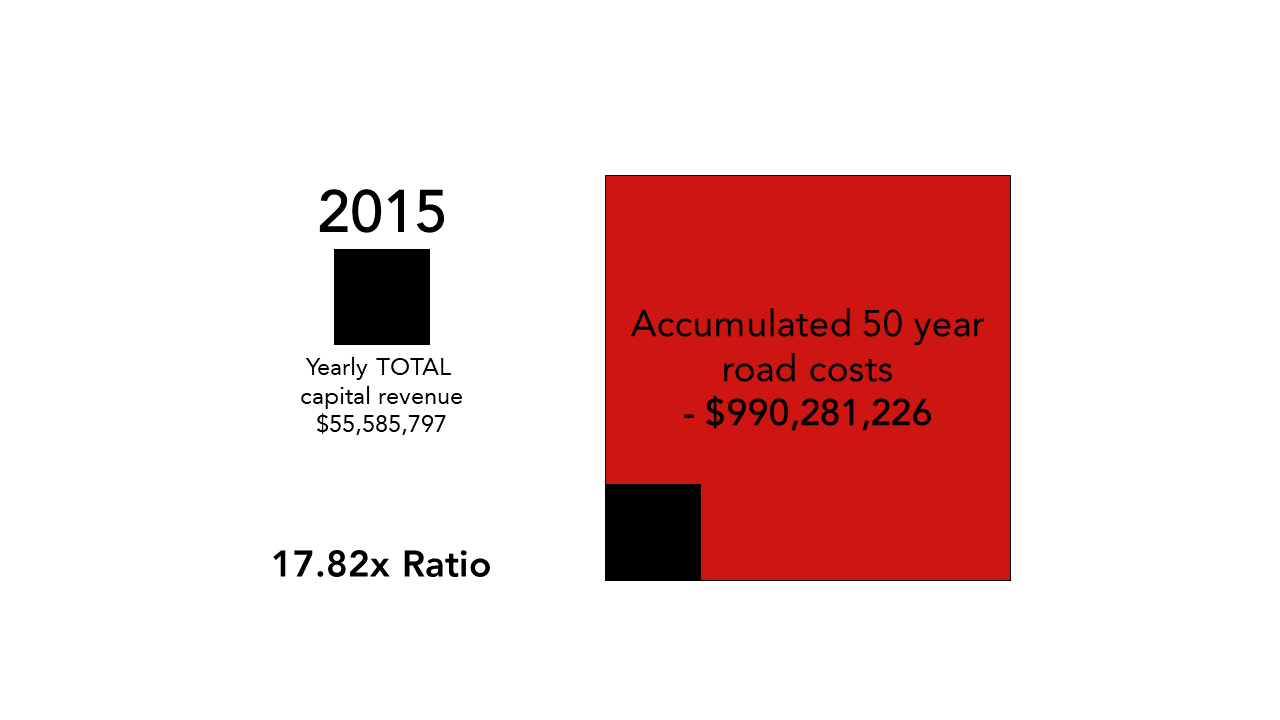

Urban3 also makes this problem clear in their next graph:

I, not an expert in tax analysis, cannot come up with exactly what the $990 million dollar count means - my best guess is that it is predicting how much it will cost to repair roads over the next 50 years, rather than being a backlog of 50 years' roads. Lafayette is home to around 120,000 people, so having 1/1000th of America’s repair backlog would be punching 3x above its weight. Maybe that’s reasonable, I don’t know.

Either way, it’s a problem. And it is a widespread problem! There is nothing particularly unique about Lafayette and its repair problems. Anywhere that has suburbs is going to come across this problem. I can nearly guarantee, outside of a few exceptions (SF, NY, DC, etc), your city has just as much an issue coming up. But it isn’t coming up now, it’s coming up later. 50 years is a long time! Surely we’ll have money by then!

It’s not a coincidence that most of America’s best suburbs are also its newest ones. One of Strong Towns’ main goals is getting cities to practice accrual accounting. This is why.

As-is, people living in suburbs are subsidized by those living elsewhere. The city has to spend more on maintaining suburbs than it collects from them, and that money has to come from somewhere. Traditionally, one imagines the affluent couple living outside city limits to be subsidizing those getting by living in apartments, but in this case it is the opposite, especially with things like the mortgage interest deduction.

Now, when I say suburbia, I don’t mean “anything but apartments.” That would be absurd. Road repair cost, presumably, scales with miles driven on them, and city density versus miles driven by each person works on a log scale: The difference between 2 people an acre and 20 people an acre is the same as the difference between 20 and 200. We do not need to get to 200; we just need to densify a little bit.

This might mean a smart suburb that has single-family houses mixed with duplexes, granny flats, and co-housing. It might mean putting small grocery stores around, expecting the neighborhood to walk or bike to it. Sometimes it means lowering or removing parking minimums. Densifying, frankly, is something one could write several books about (people have). It’s hard, for sure. One common problem is that, the moment zoning restrictions are lifted, a giant 20-story wall of concrete will appear, just because of the pent-up demand. Issues will pop up, as they always have in expanding cities incrementally. I just want to say that there are a lot of ways to do it - a lot of ways that have led to successes before.

At this point you’d probably say, “It’s perfectly fine for the city to be losing money on suburbs. The federal government and the state government can provide for the finances, and the world still comes out to a profit for having suburbs.”

I don’t necessarily disagree! Not in this point on the list, anyway. I’m just pointing out that suburbs cost a lot more than we tend to think they do. The gas tax does not even come close to paying for our roads.